The Right(est) Way To Teach Spelling (part 2)

- Aidan Severs

- Nov 6, 2021

- 6 min read

Updated: Jan 9, 2025

English seems confusing.

Did you know ‘Ough’ can be pronounced in at least ten different ways Don’t believe it? Then read the following words aloud and don’t forget to count:

cough (ough = off)

rough (ough = uff)

plough (ough = ow)

through (ough = oo)

though (ough = O)

hiccough (ough = up)

bought (ough = aw)

thorough (ough = schwa vowel)

slough (ough = uff)

lough (ough = ock/och)

This is an example of there being one grapheme (written representation) but many phoneme (sound) possibilities. (from https://theteacherscafe.com/7-mind-blowing-facts-about-english-spelling)

And did you know the ‘oo’ sound (as in ‘moon’) can be written in at least 11 different ways?

oo as in hoot

o-e as in move

oe as in shoe

ou as in you

o as in who

oo-e as in moose

ew as in new

u-e as in flute

wo as in two

ui as in suit

ue as in blue

This is an example of there being one phoneme, but many different possible graphemes. (from http://www.speechlanguage-resources.com/support-files/soundstographemesguide2.pdf) When I've challenged people to find 11 in training sessions, they often come up with examples of the 'oo' sound not listed above, often words which the English language has borrowed from other languages (more on this later). So, on the surface of things, it would seem that it is really hard to learn how to spell in English and that there is far too much variation for us to learn patterns and rules. However, this perhaps isn't the case. The long since redacted National Strategies document 'Support for Spelling' has some encouraging (old, but potentially forgotten) news for us: “…85% of the English spelling system is predictable. The keys to supporting our pupils to become confident spellers lie in teaching the strategies, rules and conventions systematically and explicitly, and helping pupils recognise which strategies they can use to improve their own spelling.” (page 5, https://dera.ioe.ac.uk/687/7/01109-2009PDF-EN_01_Redacted.pdf) So, despite the examples I gave above - the ones that certainly play into all our fears and concerns about how difficult spelling is to teach and learn - the English spelling system is predictable! Who'd have thought it? However, the same document doesn't play down English's complexity as a language: "The two factors that make English such a rich language also define its complexity: the alphabetic system and the history of the language." (page 5, https://dera.ioe.ac.uk/687/7/01109-2009PDF-EN_01_Redacted.pdf) Part of the complexity comes from the efficiency of our alphabet - those 26 letters can be used to create 44 phonemes (sounds) in 144 combinations to form about half a million words which are in current use! The fact that we only have to learn a few letters is an encouragement; the fact that they are so flexible... not so much of an encouragement. That's where those choices represented in my first two examples come in: if I want to spell 'moon', I have a lot of options for which letters to use and in which combination to make that word. Is it mune? mone? moone? (all of which you can probably find in some archaic text somewhere, from back in the days when spellings weren't so rigid!) The rest of the complexity comes from those aforementioned olden days. Most of the rest of the world has, at one time or another, influenced the English language as we speak it today. Even now, new words are coming into use - some taken from the brave new world of technology and science, others from the streets and social media. But in the past our language has benefited from three main historical sources: Germanic – From the Anglo Saxons Romance – French, Spanish and Portuguese Classical – Greek and Latin There are also words from old Scandinavian language (thank you Vikings - I especially love window = wind eye) and from when Ol' Blighty went around the world pillaging everyone else to create an empire (my favourite word in that category being shampoo).

In their journal article How Words Cast Their Spell, R. Malatesha Joshi, Rebecca Treiman, Suzanne Carreker, and Louisa C. Moats reiterate and expand on what we have already seen about predictability: "...spelling is not arbitrary. Researchers have estimated that the spellings of nearly 50 percent of English words are predictable based on sound-letter correspondences that can be taught (e.g., the spellings of the /k/ sound in back, cook, and tract are predictable to those who have learned the rules). And another 34 percent of words are predictable except for one sound (e.g., knit, boat, and two). If other information such as word origin and word meaning are considered, only 4 percent of English words are truly irregular and, as a result, may have to be learned visually (e.g., by using flashcards or by writing the words many times)." The main thrust of their article is that rote learning and using the visual memory to learn spellings is not an effective approach: "More recent studies… do not support the notion that visual memory is the key to good spelling. Several researchers have found that rote visual memory for letter strings is limited to two or three letters in a word. In addition, studies of the errors children make indicate that something other than visual memory is at work. If children relied on visual memory for spelling, regular words (e.g., stamp, sing, strike) and irregular words that are similar in length and frequency (e.g., sword, said, enough) should be misspelled equally often. But they are not. Children misspell irregular words more often than regular words." In short: we find it easier to spell the words that are more predictable and this isn't because we've remembered them visually. If we had remembered them visually, we would have remembered the more irregular words equally as well. What aids our memory is the fact that there are rules, patterns, conventions and morphological (to do with the parts of a word) and etymological (to do with where a word originated) information that help us, even subconsciously. Joshi et al go on to say: "So, if words aren’t memorized visually, how do we spell? …here’s the short answer: …Spelling is a linguistic task that requires knowledge of sounds and letter patterns. Unlike poor spellers, who fail to make such connections, good spellers develop insights into how words are spelled based on sound-letter correspondences, meaningful parts of words (like the root bio and the suffix logy), and word origins and history. This knowledge, in turn, supports a specialized memory system— memory for letters in words. The technical term for this is “orthographic memory,” and it’s developed in tandem with awareness of a word’s internal structure—its sounds, syllables, meaningful parts, oddities, history, and so forth. Therefore, explicit instruction in language structure, and especially sound structure, is essential to learning to spell." To summarise: there is a special memory system for remembering letters in words and we must deliberately teach children in order for it to develop. And the key to that teaching? Look at the part in bold: "…studies have found that effective spelling instruction explicitly teaches students sound-spelling patterns. Students are taught to think about language, allowing them to learn how to spell—not just memorize words." So... the real question is: What can we do that causes children to think about language to the point where they become good spellers? 'Support for Spelling' recommends that teachers use a spelling programme comprised of five main components:

understanding the principles underpinning word construction (phonemic, morphemic and etymological);

recognising how (and how far) these principles apply to each word, in order to learn to spell words;

practising and assessing spelling;

applying spelling strategies and proofreading;

building pupils’ self-images as spellers.

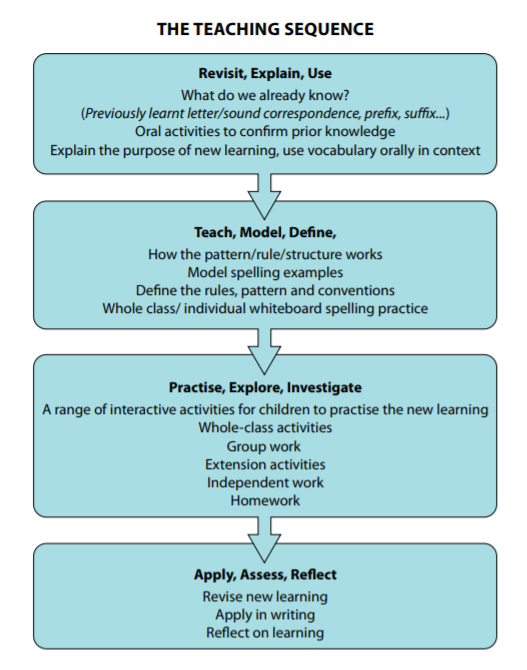

It also suggests a teaching sequence:

Joshi et al mention Linguistically Explicit Instruction and it is this that we should be aiming for. Linguistically Explicit Instruction (I'll call it LEI from now on) explicitly focuses on the links between speech sounds and spelling (or the links between phonemes and graphemes). There are probably an endless amount of ways that LEI can be done - ways which allow children to explore and think about who the graphemes and phonemes link in the English language - and the only limit is creativity.

In the third blog post we will look at what exactly might be done to ensure that the way we teach spelling is linguistically explicit. We will look at some practical activities that teachers and children can do to ensure that they are revisiting, explaining, using, teaching, modelling, defining, practising, exploring, investigating, applying, assessing and reflecting. We will look at some activities, games and tasks that go beyond the tired (and frankly not at all successful) spelling activities that have become commonplace (I'm talking wordsearches, look-cover-say-write-check and the like).

To read the rest of the parts of this series, click here: https://www.aidansevers.com/blog/categories/spelling

If you would like Aidan to work with you on developing spelling at your school, please use the contact details below or complete the contact form by clicking on the 'contact' link above.

.png)

.png)